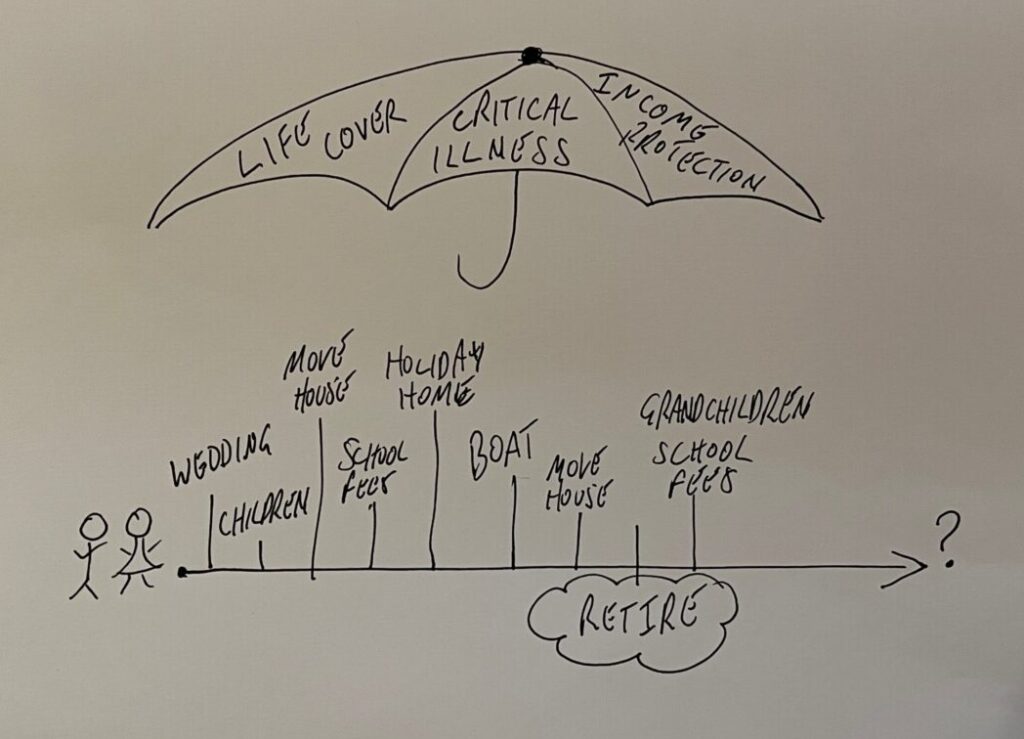

Back in the ‘80s, in the days of large direct salesforces from the likes of Prudential, Equitable and the MI Group, there wasn’t really much financial planning being done because it was all about product sales. So instead of being taught financial planning skills, new entrants to the financial services industry were taught sale skills and given sales tools. One of those sales tools was the concept of a Lifeline and a Protection Umbrella.

Funnily enough there are many similarities between those and the modern Lifetime Cashflow systems. You sketched out a potential client’s Lifeline and then worked with them to put milestones and objectives along that line with the aim of then selling pensions and savings plans to those objectives. Then over the whole line you drew the Protection Umbrella, because without that if something happened to you then the goals and dreams would not be achieved. Into that Umbrella then went life cover, critical illness cover and income protection.

The aim was to create a series of wants and then a number of problems to which you could sell solutions – three more sales if you were lucky and with chunky up front commission payable.

The concept was not inherently a bad thing; talk with someone to get them to visualise their goals and dreams, quantify them, look at the shortfalls and set milestones; talk about the tough stuff, dying too early, living too long, being too ill or disabled to work; create a plan for how they can achieve what they want to achieve and avoid the things that might prevent them from doing so. I could be describing one version of a modern financial planning process.

Meanwhile, financial planners were having to work with Excel spreadsheets to construct financial models for clients, printed out on A3 paper, with no fancy graphics. This was the professional end of the spectrum where things were about analysing what clients wanted and what they had and projecting using reasonable assumptions to create a road map to help them get from A to B.

These days there are numerous systems that facilitate this type of planning, remove the necessity for complex formulae tied to tax allowances and rates, and add in lots of pretty graphics and the ability to make changes “on the fly” to test out what would happen if …..

For a financial planner this is great.

Being able to put all the data you need into a system simply and (relatively) easily, with the system built holding all the tax information necessary and with simple ways to model different methods of drawing from pensions and investments means not having to know that it is cell AC97 that need to be amended for each new model.

Being able to produce a myriad of different graphics, as well as tables, means being able to work with the different ways in which people think best.

Being able to move a retirement date or change a gift amount and have the system adjust in a second and then allow you to show two graphs, a before and after, next to each other, means conversations about “what if ..” and “can we afford to …” become easy and valuable to a client.

As the cashflow systems have proliferated they have gradually moved from something that largely differentiated a financial planner from a financial salesperson. They went from needing time and expertise to put into the model construction to just needing enough knowledge to know what figure to put where and which button to press to get a report out.

The regulator is already showing concern over the use of assumptions in cashflow models as their use expands. Assumptions of longevity or investment returns, if not relevant and reasonable can either make things look better than they are or be used to convince someone they have to push lots more money into pensions and investments if they are to survive in retirement for example. So it is important to be clear about what the assumptions are, ensure they are relevant, realistic and relate to each other in a sensible fashion.

One of the dangers of a cashflow model is that, even if you are confident that the assumptions are reasonable, it can be too easy to think that it is showing you something definite. In reality the only thing that is certain about a cashflow is that it is wrong. There are assumptions in the model and once you have even one assumption what you have is going to be wrong. The only question really is how wrong.

As cashflow systems move from being the exception to becoming the norm, increasingly the question has to be not “do you offer cashflow modelling” but “what are you using cashflow modelling for”. Are you using reasonable assumptions to enable us to model different options and help us make decisions about how we want our life to turn out, or are you producing a pretty graph, with a big figure at the end for Inheritance Tax and selling us an expensive life assurance policy as a solution to a problem that doesn’t really matter to us?

A tool is just that, a tool. How that tool is used is what is important.

The Financial Conduct Authority does not regulate Cashflow Planning